The shrinking of large lakes in southern Tibet may be directly contributing to seismic activity in the region, according to new research published in Geophysical Research Letters. Geologists have discovered a compelling link between water loss from these ancient lakes and the reactivation of dormant geological faults, suggesting that climate-driven changes can influence deep-Earth processes.

The Weight of Water and Shifting Crust

For millennia, southern Tibet was home to vast lakes, some stretching over 200 kilometers in length. Today, these bodies of water have dramatically decreased in size – Nam Co Lake, for example, has shrunk from its original size. This reduction in mass has a measurable effect on the Earth’s crust. Large lakes exert significant downward pressure; as they dry up, the crust slowly rises, similar to how a ship lifts when cargo is removed.

This process isn’t merely theoretical. Southern Tibet sits in a geologically active zone where the Indian and Eurasian plates collide, creating immense strain within the Earth’s crust. Over millions of years, this pressure has formed ancient cracks (faults) primed for rupture. The rising crust caused by vanishing lakes appears to be triggering these ruptures, resulting in earthquakes.

How Much Movement?

Researchers analyzed ancient shorelines to determine the extent of water loss. Their models indicate that the shrinking of Nam Co Lake alone contributed to approximately 15 meters of movement on a nearby fault between 115,000 and 30,000 years ago. Lakes south of Nam Co show even more drastic changes, potentially causing up to 70 meters of movement. This translates to an average of 0.2 to 1.6 millimeters of fault movement per year. While less than the San Andreas Fault (around 20 millimeters annually), this demonstrates that surface processes can meaningfully impact tectonic activity.

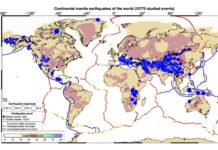

Beyond Tibet: A Global Phenomenon?

The findings challenge the traditional view that earthquakes are solely driven by deep-Earth processes. Matthew Fox, a geologist at University College London, emphasizes that “surface processes can exert a surprisingly strong influence on the solid Earth.” This means that events like glacial melt, erosion from storms, or even human activities like quarrying – which removes large amounts of rock – can alter stress conditions within the crust.

The most substantial example is the ongoing rebound of landmasses previously covered by massive ice sheets during the last glacial maximum (around 20,000 years ago). As these ice sheets melted, the crust began to rise, and continues to do so today. This uplift may explain some mid-plate earthquakes, such as the powerful quakes that struck the Mississippi River Valley in 1811-1812. The theory suggests that centuries of accumulated stress released when the land rebounded after the ice melted.

“Climate change does not ’cause’ tectonics, but it can modulate stress conditions in the crust,” Fox explains. This underscores the need to consider surface-deep Earth interactions in future hazard assessments.

The study demonstrates that the connection between climate and geology is stronger than previously thought. While tectonics remain the primary driver of earthquakes, changes in surface load can significantly influence how and when that stress is released.