For over 100 years, astronomers have grappled with a fundamental question: how fast is the universe expanding? This enduring debate, often called “Cosmology’s Great Debate,” began in the 1920s and continues today, not because of lack of data, but because of conflicting measurements and the potential need for entirely new physics.

The First Great Debate: Galaxies Beyond Our Own

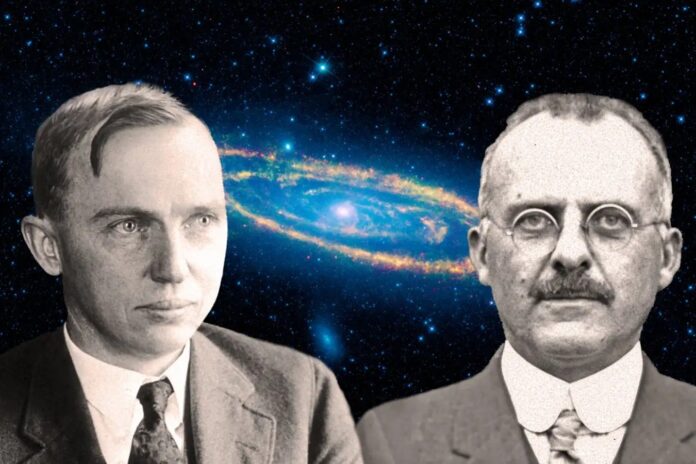

The initial clash arose from a simple question: were the faint “spiral nebulae” observed in the night sky simply clouds within our own Milky Way galaxy, or were they entirely separate galaxies beyond our own? In 1920, Harlow Shapley and Heber Curtis engaged in a public debate at the US National Academy of Sciences, with Shapley arguing for a relatively small universe dominated by the Milky Way. Curtis countered that these nebulae were “island universes” – independent galaxies at vast distances.

Curtis was proven correct when Edwin Hubble later confirmed that these nebulae were, in fact, galaxies beyond our own. This discovery dramatically expanded the known scale of the universe, shifting from a localized view to one of cosmic immensity. However, even after this resolution, the debate over how quickly the universe was expanding had just begun.

The Hubble Constant and Early Discrepancies

Hubble himself proposed the “Hubble constant” in 1929 – a number that quantifies the rate of cosmic expansion. His initial estimate was around 500 kilometers per second per megaparsec, implying a young universe. However, this value immediately presented a paradox: if true, the universe would be younger than some of the oldest rocks on Earth, which was impossible.

By the 1980s, astronomers fell into two opposing camps: Gérard de Vaucouleurs, who favored a Hubble constant near 100, and Allan Sandage, who argued for a lower value around 50. Both used similar methods but stubbornly refused to concede ground.

The Hubble Key Project and Renewed Conflict

The launch of the Hubble Space Telescope in the 1990s brought new precision. Wendy Freedman led the “Hubble Key Project,” refining measurements to a value of approximately 72 kilometers per second per megaparsec. For a time, it seemed the debate was settled, with converging data pointing towards this number.

Yet, a new conflict emerged in the early 2000s. Measurements based on the cosmic microwave background (CMB) – the afterglow of the Big Bang – yielded a significantly lower value: around 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec. This discrepancy, known as the “Hubble tension,” has persisted despite increasingly accurate measurements on both sides.

The Modern Great Debate: A Deeper Mystery

Today, the Hubble tension remains unresolved. The two methods, local distance measurements and CMB analysis, continue to disagree. This suggests several possibilities: systematic errors in one or both methods, or the need for entirely new physics beyond our current understanding of the universe.

Astronomers are now exploring independent methods, such as analyzing gravity waves and using different types of stars to refine measurements. The debate rages on, not as a matter of simple disagreement, but as a sign that our fundamental understanding of the cosmos may still be incomplete.

The ongoing quest to measure the universe’s expansion isn’t merely an academic exercise; it’s a search for the most accurate picture of reality itself. The persistence of the Hubble tension suggests that the universe may hold surprises far beyond what we currently imagine.