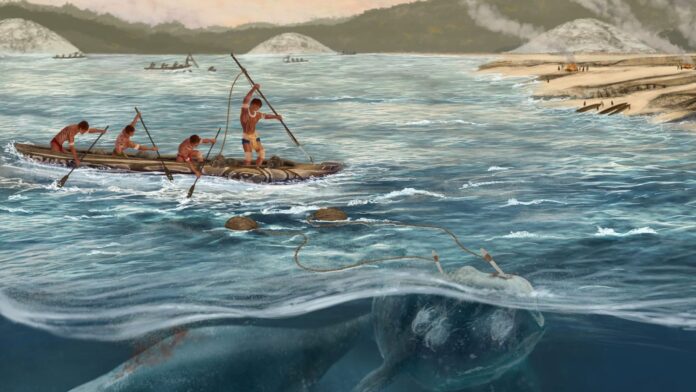

New archaeological evidence from Brazil’s southern coast reveals that organized whale hunting began at least 1,500 years earlier than previously understood. A study published January 9 in Nature Communications details the discovery of 5,000-year-old whalebone harpoons and butchered remains within ancient shell mounds, challenging the long-held assumption that whaling originated in the Arctic and North Pacific. This finding doesn’t just shift the timeline of whaling, but also suggests that humpback whales historically inhabited regions they’ve long since abandoned.

Challenging Existing Theories

Until now, the consensus was that systematic whaling emerged between 3,500 and 2,500 years ago in the frigid north, driven by food scarcity. South American whale bones were generally dismissed as the remnants of scavenged carcasses. However, the newly unearthed artifacts – including specialized harpoon heads crafted from whalebone, butchered skeletal fragments, and other whalebone tools – conclusively demonstrate deliberate, large-scale hunting.

The Sambaquis: An Unexpected Archive

The evidence comes from sambaquis, massive shell mounds along the Brazilian coast. An amateur archaeologist began collecting over 10,000 objects from the Babitonga Bay area in the mid-20th century to preserve them from urban development. These mounds, some reaching 30 meters in height, served as both landfills and burial sites, with the dead often interred alongside crafted whalebone objects. Re-examining this forgotten collection revealed a striking abundance of whale bones, far exceeding what could be attributed to chance.

Proof in the Bones

“There’s an absurd amount of whale bones in these mounds,” explains archaeologist Andre Colonese of Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. The discovery of identical, pointed bone sticks confirmed their use as harpoon heads. Subsequent laboratory analyses dated the artifacts to 5,000 years old. Protein analysis of hundreds of whalebone fragments identified southern right whales as the primary target, but also revealed evidence of humpback whales and dolphins. The presence of humpbacks is particularly significant, as they’ve been absent from this region for centuries.

Ecological Implications

The findings offer a unique glimpse into Brazil’s pre-colonial ecology. Humpbacks were likely driven out by intensive whaling during the 17th and 18th centuries, and their recent, tentative return may represent a recolonization of historical habitat rather than a simple population shift. This distinction is crucial for conservation. Knowing that humpbacks historically ranged as far south as Babitonga Bay supports the idea that their current re-emergence is a natural recovery rather than an anomaly.

A Global Pattern

While similar protein studies have been conducted in Europe and North America, this research represents a breakthrough for the Southern Hemisphere. Zooarchaeologist Youri van der Hurk notes that exploiting whales near settlements was widespread when feasible. Southern right whales, which linger near shore with calves and float when deceased, would have been particularly vulnerable.

Why It Matters

The study challenges the assumption that early humans in resource-rich environments like Brazil wouldn’t engage in whaling. A single whale provided months of food, oil, bones for tools, and other valuable materials, making the risk worthwhile. The research team plans to survey other areas along the Brazilian coast, anticipating similar evidence across the Americas. By cataloging pre-colonial whale species distribution, they aim to provide concrete data for conservation efforts. As Colonese states, the goal is to inform policymakers: “Look, these are the species that were here.”

This discovery underscores that human impact on marine ecosystems is far older and more widespread than previously assumed. By rewriting the history of whaling, scientists are also strengthening the case for restoring historical ranges in modern conservation strategies.