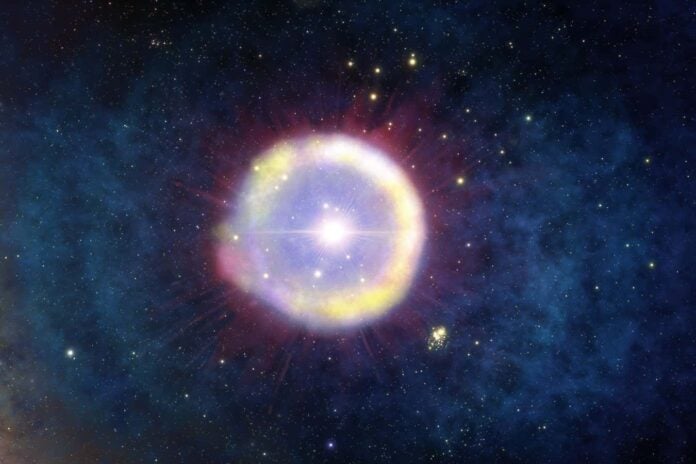

Astronomers may have identified the most promising candidate yet for Population III stars – the first generation of stars to ignite after the Big Bang. These primordial giants have been a long-sought goal for researchers, and recent analysis of distant galaxy LAP1-B offers a tantalizing clue.

What Were Population III Stars?

Unlike the stars we observe today – known as Population I – Population III stars are theorized to have formed in a drastically different environment. They emerged from primordial gas composed primarily of hydrogen and helium, before the universe had dispersed heavier elements through supernovae and stellar winds. As a result, these first stars are predicted to have been significantly larger and hotter than their modern counterparts.

The LAP1-B Galaxy and Gravitational Lensing

The potential discovery centers on observations of LAP1-B, a distant galaxy located at a redshift of 6.6. This redshift indicates that we are observing LAP1-B as it existed just 800 million years after the Big Bang – an astonishingly early stage in the universe’s evolution. Spotting such a distant object was only possible due to a phenomenon called gravitational lensing. A closer cluster of galaxies acted as a cosmic magnifying glass, bending and amplifying LAP1-B’s light, making it visible to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

“The universe is filled with these primordial star formations,” explains Eli Visbal at the University of Toledo. “However, we can only really examine the universe under the light of gravitational lenses, which act like cosmic spotlights.” Visbal and his team’s calculations suggest that at this redshift, there should be roughly one Population III star cluster – precisely what they’d observed in LAP1-B. Their abundance estimate perfectly aligned with previous findings indicating a single cluster.

A More Realistic Size?

Another point bolstering LAP1-B’s status is its relatively modest stellar mass. Estimates suggest it’s only several thousand times the mass of our sun – a lower mass than most other candidate galaxies for Population III star populations. Simulations of early star formation suggest that clusters of Population III stars should have been significantly more massive. “This is the most convincing candidate we’ve seen so far,” says Visbal.

Scepticism and Future Observations

Despite the excitement, some researchers remain cautious. “LAP-B1 is an extremely interesting candidate, but it’s far from showing the clear, unambiguous signs we’ve been searching for,” says Roberto Maiolino at the University of Cambridge. It would require an extremely rare combination of factors to have resulted in Population III stars at this late stage.

However, it remains possible that pockets of pristine hydrogen and helium could have lingered longer, enabling Population III stars to form later than previously anticipated. Ralf Klessen at Heidelberg University adds, “Statistically, this would be a significant outlier.”

Why This Matters

Understanding Population III stars is critical for unraveling the universe’s evolution. These primordial stars were responsible for synthesizing the first heavy elements – the building blocks for everything we see today. “They can tell us how the chemistry of the universe evolved from just hydrogen and helium to all the complex ingredients needed for life and the cosmos as we know it,” explains Visbal. The discovery of Population III stars would provide invaluable insights into the universe’s earliest stages and the origin of the chemical elements that make up our world.

Journal reference: The Astrophysical Journal Letters DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/ae122f