A newly re-examined fossil from the Cambrian period (roughly 540 million years ago) provides compelling evidence that Hallucigenia, one of the most bizarre animals ever to exist, was likely a scavenger. The discovery suggests a feeding behavior previously unknown for this early life form: a swarm of these creatures consuming the remains of a dead comb jelly. This changes our understanding of how life thrived in deep sea environments during the Cambrian explosion, when many animal groups first emerged.

The Enigmatic Hallucigenia

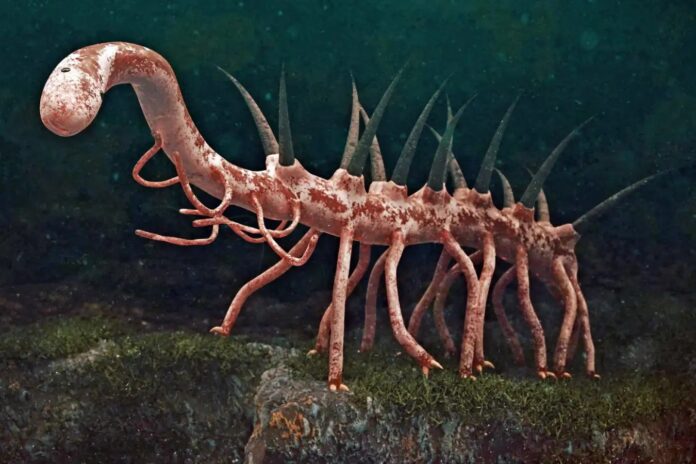

Hallucigenia was a small (up to 5 cm long) worm-like animal characterized by multiple legs and sharp spines along its back. Its unusual anatomy led to initial misinterpretations, with paleontologists reconstructing the animal upside down, mistaking the spines for limbs. The fossils were first discovered in the Burgess Shale deposits of British Columbia, Canada, and are related to modern velvet worms, tardigrades, and arthropods (including insects and spiders).

For decades, one of the biggest mysteries surrounding Hallucigenia was its diet. No preserved gut contents have ever been found in fossils, leaving scientists to speculate about its food sources. This is significant because understanding an animal’s diet reveals how it fits into its ecosystem.

A Snapshot of Ancient Feeding Behavior

Javier Ortega-Hernández at Harvard University re-examined a fossil dating back to the original 1977 description of Hallucigenia. The fossil contains the severely damaged remains of a comb jelly (ctenophore), measuring 3.5 cm by 1.9 cm. Scattered across the comb jelly were spines identified as belonging to seven Hallucigenia individuals.

Ortega-Hernández proposes that the comb jelly died and sank to the seafloor, attracting the Hallucigenia swarm. They likely fed using suction, quickly consuming the soft-bodied prey before being buried in mud and fossilized. This is a rare and valuable find: a moment frozen in time, demonstrating an ecological interaction that may have lasted only minutes or hours.

Debate and Alternative Theories

While paleontologist Allison Daley at the University of Lausanne calls the evidence “convincing,” some experts remain cautious. Jean-Bernard Caron at the Royal Ontario Museum suggests the proximity of fossils doesn’t necessarily prove interaction; undersea mudslides could have deposited them together. Caron also raises the possibility that Hallucigenia may have shed its spines as part of a molting process, rather than actively feeding on the comb jelly.

The scarcity of nutrients in the deep sea makes scavenging a plausible survival strategy for Hallucigenia. Suction feeding would be particularly effective at consuming soft-bodied organisms like comb jellies.

This discovery highlights the challenges of reconstructing ancient ecosystems. Paleontological evidence is often fragmented, leaving room for interpretation. However, this new fossil adds a crucial piece to the puzzle, providing a clearer picture of Hallucigenia ‘s role in the Cambrian food web.

Ultimately, the fossil record is rarely complete. But such finds remind us that even the strangest creatures of the past had to eat to survive.